Newsletter: Navigating the Maze

Sample chapter and preorder info for Company of Ghosts

It’s been a pretty good week.

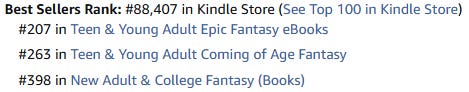

As most of you probably know, the Kindle link for Company of Ghosts went up on Amazon last Thursday. Since then, the number of preorders has already driven it into Top 200 territory for a few categories.

I’m having trouble wrapping my head around that. No agent, no publicist, no real social media presence. It’s only been on sale for a few days, and it won’t be out for another month. I haven’t even posted an excerpt yet.

But the numbers keep moving.

The explanation, of course, is you, Dear Reader. This weird little community of supportive friends and internet strangers who read my stories every month and are willing to toss a few bucks into the pot to help make a dream come true. Gratitude is the only word that begins to cover it. Heartfelt thanks to everyone who’s preordered and helped spread the word.

As some folks have already pointed out, the physical copy isn’t available to preorder yet. It should go live on the release date (September 16th), but Amazon doesn’t do preorders for physical books that are published through KDP. I wish there was a cleaner way to get my book everywhere I want it to be, but distribution is a labyrinthine hellscape filled with roided up minotaurs, and I’m running out of thread.

We’ll get there eventually. The goal is to have physical copies in libraries, multiple digital formats, and the beginnings of an audio book by the end of the year, minotaurs be damned.

One last item of housekeeping before we get to the sample chapter. As mentioned on my Terms of Use page, the fiction I post here is available under the CC BY-ND 4.0 license unless otherwise indicated. The chapter below is one of those exceptions, and is not published under CC BY-ND 4.0. All rights are reserved by me, the author and copyright holder. You may not transmit, remix, or redistribute any part of the work. If you’d like to help get the word out, please do so by linking directly to this page or clicking the convenient little share button below.

With that out of the way, here’s the first chapter of Company of Ghosts. It’s a long one, so make yourself a cup of tea and get cozy.

Sample Chapter for Company of Ghosts

I collected secrets as a child. From my perch behind the counter, I could hear every word spoken in my father’s little shop, and I repeated all of them. I didn’t yet understand that there was such a thing as a private conversation, that it was rude to be interested in the details of a stranger’s life.

My father had a very practical solution to the problem. Mind the shop. He repeated the phrase any time I tilted my head toward a whisper or spent too long tidying a display and sent me scurrying off to a far corner to sweep some imaginary dust across the floor. I think he feared I’d grow up to be a gossip. Considering my career as a historian, he might not have been far off. The line between rumor and history is frighteningly thin.

In any case, half the fault lies with him. He had so many secrets of his own, and as the only parent, he had twice the practice at deflecting my curiosity. With so little bread at home, it was only natural that I’d go looking elsewhere for crumbs.

I had a different solution to the problem, of course. As far as I could tell, secrets were only dangerous when you shared them. Knowing a secret hurt no one and was immensely satisfying in its own right. I was still too young to have learned that bitter lesson, that knowing a thing could be dangerous, too. Meeting Andza changed all that, and as fate would have it, I was alone in the shop when he came in.

◆◆◆

The door swung open one evening, and a rush of cold air swept in. All the display candles along the back wall flickered and guttered out. My father had told me to put the covers on them, and as usual I had forgotten. The back wall of the shop was thrown into dimness, full of thin tendrils of smoke just visible in the light from the street. The door swung closed, and the man in the doorway crossed the floor to stand in front of my father’s counter.

“How much for a wax candle?” he asked.

“Six peras,” I told him, already drinking him in. He stood somewhere around six feet, maybe less, with close-cropped hair and a thin layer of stubble. Plain clothes, but tidy. Thin in the way that a tightened string is thin, all full of quiet energy.

“Are those unscented?” he asked. “I need a steady light, not a bottle of perfume.” He was impatient, I thought, though not with me.

“Eight for the unscented,” I told him. Then, catching his expression, “We save on the oils, but the wicks are harder to make.”

“Yes, fine. I’ll take two.”

He paid, and I wrapped his purchase and tied the paper with a length of string. He tapped the side of his thumb against the counter while he waited, and the motion distracted me so much that I had to restart. When I finished, I handed him the package. He turned to leave but then hesitated.

“What’s your name, child?” he asked me, one hand still on the counter.

“Jalina.”

“Good night, Jalina,” he said. And then he left.

Afterward I sat on the little stool behind my father’s counter and replayed all the details of the conversation in my head, a habit I’ve never really grown out of. After half an hour my father returned from his errand and made me relight all the candles that had blown out. We stayed open for another hour and then went upstairs to eat a late supper. Father worked while he ate, whispering to himself about the shop or about money that we didn’t have, which left me free to sit quietly and ponder. I thought about the man I’d met and the short conversation we’d had. I decided that I liked him, though I didn’t yet know his name.

◆◆◆

The next morning there was a knock at our door.

I slept on the very top floor of our house, in a little loft by the window, so I barely heard the noise. My father stirred, then walked downstairs. I waited until I heard voices, then put on the little house slippers we wore in the winter and crept down the ladder to the main floor. From there, I tiptoed past our sleeping cat and leaned over the staircase that led down into the shop.

“—would have been about thirty or forty, not from around here.”

It was the constable, talking to my father. About what, I couldn’t guess, but I knew it had to be something important. People from other nations might not understand the significance of this. Contrary to popular belief, we do have petty saints in Kerra. A large town like Casmhe would have at least one Reader to perform basic acts of divination, but law and long custom prevented them from interfering with matters of state. As state officials, our constables did their work by going door to door.

“I could try to make a list, if you like. We couldn’t have had more than twenty or thirty customers yesterday.”

“And you recognized them all?” The constable spoke crisply. He likely had other stops to make. “No strangers?”

“None,” my father answered.

“Then that’s enough. Sorry to bother you.” A moment later the door opened again and swung closed.

I heard my father’s footsteps approach the stairs, and I rushed to the stove to make some tea so that I’d have an excuse for being up and about. He said nothing when he saw me, only kissed the top of my head and sat on the edge of his mattress.

“Who was downstairs?” I asked.

“An angry customer. He said you’d given him the wrong change.”

“No, it wasn’t!” I shot back. But then I saw him smiling and realized he’d caught me.

“Sorry.”

“A proper father would scold you, but you’re making tea, so I suppose I’ll have to forgive you.”

The kettle reached a boil, so I quieted the flame and poured the water into a small teapot. When it had steeped, I poured two cups and handed one to him. He set it on his nightstand to cool.

“What did he want?”

“Only to ask if I had any little girls who asked too many questions. It’s against the law now, you know.” A favorite joke of his. He always found it funny. I never did.

“Father!”

“Only joking, little one.” He smiled briefly, then frowned. “Lina . . . Did you sell anything yesterday while I was out?”

I felt a sudden urge to lie. My father held so many secrets of his own—secrets I felt I had every right to know. Whenever I asked him about his life before the war, or about my mother’s death, he refused to answer. But he expected me to give my secrets away just for the asking?

It was futile, though. He would find out as soon as he checked the ledger. “Two candles,” I said. Then, struck with a sudden inspiration, “Warren came to pick some up just before you came back.”

Warren was the clerk’s assistant. He was two years older than me, born mute after a difficult pregnancy. He’d become a ward of the city after his parents passed and sometimes ran errands. I told the lie smoothly and hoped my father wouldn’t notice.

But he was already drinking his tea. “Good,” he said, his eyes closed and his nose just over the rim of the cup. “Otherwise, I’d have to chase poor Gellin down the street and tell him my daughter was an accomplice to murder.”

◆◆◆

Guilt weighs heavily on me. I suppose it does for everyone, but as with other skills, things are easier for those with natural talent and years of practice. At the time I had neither, so I worried constantly.

For a month I believed they would catch him at the border, still carrying the murder weapon. They’d torture a confession out of him and drag him back to Casmhe behind a pair of mules. There would be a trial, and in madness and desperation, he would name me as his accomplice to lessen his own sentence.

I saw the ripples of shock spread through my friends and neighbors in the crowd, heard my mother’s desperate wailing (my mother featured constantly in my daydreams, though she died when I was an infant). I saw my father wrap an arm around her and bury his head in shame, and I hated them both for excluding me in their grief.

Later we found out there was no murder weapon. The sole witness, an old woman who lived across from poor Miss Talia, had only thought she’d seen an upraised arm on the strange and fearsome silhouette. The vicious broadsword, the hacked-up body: we had invented these details ourselves. The magistrate had released the report to silence our guesses.

No, the late Miss Talia had not been the subject of any violence. Yes, a strange man had forced his way into her apartment. No, he hadn’t stolen anything. By all appearances they had surprised each other, the victim’s heart had given out, and the would-be thief had fled the scene.

But rumors are pernicious things. They’ll cling to bare rock, if they have to. Besides, we still had the questions of “Who?” and “Why?” to occupy our thoughts. Was he merely a thief, or was there something more to the story? Was he a spurned lover who had tracked her down? An angry brother who had been cheated out of his inheritance? An abandoned son who had come seeking closure? Talia had been mysteriously private, so all theories were possible, and none could be proved or disproved.

In the end, the rumors died down the way most do: simple repetition. The moment someone hears an old version of the tale, the first death knell is sounded. By the end of the week, the coffin is closed, the earth shoveled over, and the marker erected. Two months after her death, everyone seemed to forget that Talia had lived or died.

Except for me, who had helped to kill her.

◆◆◆

I passed these dismal days in the pages of books. No lurid dramas or tales of suspense. My imagination conjured enough of those already. But I couldn’t quite rid myself of my interest in people, of their daily lives and habits. I read biographies instead: personal accounts, diaries, letters. All were of famous people, like the Dowager Empress of Ghant or the chief concubine of the Hensian Talarch. I spent more time at the library than I did at my own home and often hid a book or two under the counter to read while I worked. In the space of three months, I learned about the fall of the Red Empire, the northern expeditions of the previous century, and the lives and deaths of a few dozen famous rulers from the past six hundred years.

My father noticed the change in me. “Where has my little bird gone?” he asked one evening. “She used to sit behind the counter, just there, and tilt her head to listen every time someone spoke.”

I turned the page of my book but didn’t look up. “She must have flown away, Father.”

He crossed the room to where I sat and lifted my chin. The candles behind him wavered, but every detail of the room was crystal clear. “And where would you like to fly, my little one?”

I didn’t answer. I just sat there staring back at him. I couldn’t understand what he meant. I was fourteen years old, and no one had ever asked me that question before.

“I don’t know,” I said finally. “I suppose I’ll learn to run the shop.”

◆◆◆

Spring came, and with it the promise of warmer weather. I’d made good on my promise to learn my father’s business, and so the shelves of our little shop were always stocked, always tidy. I enjoyed the routine of running the shop: so many hours for this task, so many for this one, until the whole day was filled with work that was neither too hard nor too easy.

It brought me closer to my father, too, which was something I didn’t properly appreciate at the time. Though we lived in the same house, I’d always considered his world as something apart from mine. But for a season at least, the gap vanished, and I grew closer to him than I ever had before. Which made what came next even more surprising.

We’d closed the shop early after a slow morning, and the two of us sat down at the table together over a plate of cold sandwiches and a pitcher of cider. My father looked at me as he spoke.

“The Reader says the rains have stopped for the season. The road south should be passable within a week or two.”

“Are we going somewhere?”

He took a sip of his cider. The rim of the cup hid his expression. “I thought we might take a trip to the town of Sharme. We need to get there early, before enrollment closes, or you’ll have to wait until the fall.”

I had no idea what to say. I think I stammered something unintelligible.

“I’ll be fine in the shop. And anyway, you needn’t be gone longer than a year. And you’ll be quite safe, I think. Sharme itself is not so much larger than Casmhe.”

And in the space of a breath, my father had quieted all my fears, long before I ever gave voice to them. People often say that I have a knack for listening to people, for peeling away their many layers and seeing what lies beneath. If I have any gift at all, it is surely inherited.

“But what about—” I trailed off. Surely there had to be something. “What about all my clothes?” I finished. “What will I wear?” I must have seemed stupid, more flighty girl than somber scholar. But my father laughed.

“Space for them on the wagon, little one. And a few books, too, I should think. Though I can’t imagine you’ll need them. The Library must have plenty of their own.”

◆◆◆

I won’t bore you with the details. Suffice it to say that I passed my entrance exams and enrolled as a student. I missed my father terribly at first but less and less as the months passed. I loved my classes and got along well with most of my classmates. I spent countless hours in the city itself, wandering Sharme’s maze of streets before coming home each night to the little room that I didn’t have to share with anyone else.

I chose to study history, with a focus on ancient civilizations. Even now, I can’t imagine a less useful way to spend one’s life. But that didn’t bother me at the time, and anyway, no one in academia will ever dissuade you from wasting your life on something. If anything, I developed a reputation as a model student. For the first time in my life, it was safe to be who I was. My curiosity was a virtue, not a vice.

Best of all, the night of Talia’s murder seemed to fade with each passing month. I could remember the details, but there wasn’t any weight attached to them. It was as if I’d carried the memory with me to Sharme but left the guilt behind in Casmhe.

◆◆◆

Every summer, the teachers at the Library hold assessments, which all students must endure. First-year students need only demonstrate a reasonable amount of progress in their chosen discipline. But for the older students, the second and third years especially, assessments mark a time when you’re pushed to pursue a narrower focus.

Once you make that choice, your life changes considerably. Certain areas of the Library become open to you, while others are rarely ever visited again. Your teachers shrink down to two or three veteran scholars, and you and your classmates become so busy that you’re reduced to nodding at each other in the hallway over your armful of books.

My assessors were a pair of modest historians, Dran and Liseth, a married couple well into their sixth decade together. They bickered constantly but without any real heat. I enjoyed them both immensely. The classroom where we met occupied half the third floor of the teacher’s wing, with fresh breezes and pleasant views at every window. A stack of desks sat in the corner, unused for years but kept against the possibility of a surge in enrollment. A crate of talc pencils beneath the north window gave the air a musty, dry quality. Despite the humble surroundings, I fidgeted beneath the weight of the proceedings.

“You’ll need to master your Ghant, of course. Your grasp of the lower forms is faltering at best, and don’t think I haven’t noticed.” This from Dran, who fixed me with a look like a vulture daring the carcass to move. I didn’t.

“Once you stop speaking the language like a child,” he continued, “you can get into the real texts. Gramme the Blind has a three-volume set that’s worth reading. He was an idiot, but he was the only one paying attention when the Hensian Empire started, and no small irony there.”

Liseth interrupted him with an irritated gesture, slashing the air in front of her with a liver-spotted hand. “Bah. Reading, reading. Are we scholars or buzzards, circling the same dead things year after year? Where are you from, child?”

“Casmhe,” I said. “A small house on the merchant’s row, not far from the town center.”

“And how long would you say the road is between Casmhe and Sharme?”

I smiled. “Just long enough to reach, I think.”

She cackled, a harsh, unpleasant sound. “Good, that’s good. The world has plenty of uses for witless girls, and none of them are worth your time.” The smile disappeared. “You’re not seasoned yet, though, and I won’t inflict another naive scholar on the world. Too much room for pretentiousness to creep in, eh?” She shot a pointed look at her husband, who frowned.

“The point is,” she continued, “there’s a great deal of difference between knowing the lines on a map and walking them. You can’t be the next Gramme if all you ever do is read about him.” She folded her arms, a sure sign she’d chosen a course. “I have an acquaintance named Andza.”

Dran snorted. “Ah, yes. Our itinerant scholar.”

“Itinerant?” I asked.

“Homeless, if you prefer. Sleeps in a wagon, teaches a course every three or four years. Doles out mountains of assignments and then leaves again before grading any of them.” Dran looked thoughtful. “He’s either an idiot or a genius, and I’ve never decided which.”

“He may be an idiot,” Liseth allowed, “but he pays attention, and no small irony there.”

Dran rolled his eyes.

I held back a smile, a study in polite curiosity. “What does he teach?”

Liseth grinned like a fox. “Speaking as a member of the committee that approves his research stipend, he’ll teach whatever we damn well want him to. More importantly,” she leaned forward, “he’s recently requested a pair of research assistants from among the students here. Make sure you’re one of them. I’d hate to see the opportunity wasted on someone else.”

This led to an argument: how many years I’d fall behind, what books I’d have to bring on a journey, whether I’d bring any books at all, how I could possibly continue my education in the dimly lit common room of a noisy inn. The afternoon light reached in through the window and warmed my shoulders, and the rhythm of their conversation lulled me into a kind of daydream. I fell to musing. Andza, I thought. What a curious name.

◆◆◆

And so my secret guilt came back to haunt me and, with it, the story you now hold in your hands. Interested? I’d be surprised. Even as forewords go, this one is remarkably indulgent. I’ll acknowledge the touch, though, if you’ll allow me an explanation.

Andza’s book summarizes the story I’m about to tell in one neat, efficient sentence.

It reads:

And so I set out from the Library at Sharme with two assistants, seeking the answers to several unanswered questions behind the latest war of succession.

No indulgence there, you’ll notice. Every word is carefully chosen, stripped of all emotion and judgment. No comments on the all-too-common melees between Kerra’s bloodthirsty princedoms. No names, when the mention of assistants gives all the necessary context. No “hoping” when “seeking” will suffice.

That opening line was Andza to the letter. Spare, unyielding, precise.

And yet, you can almost picture the man behind the prose. A bit too serious, perhaps. Uncommonly driven. The kind of man who would sneak into a home to question a woman about secrets she’d long thought buried. Someone who could remember every detail of the conversation for the rest of his life, constantly arranging them until the full picture emerged. A man who wouldn’t hesitate to trade a fortune for a fact, a scar for a whisper. Fearless. Heroic, in his own quiet sort of way.

This book is not written as a counterpoint to Andza’s work, but as a complement. To fill in the details that were too unimportant for the original, too insufficient in gravity and meaning. To give names to the people history forgot to include, and to explain, I hope, why we chose to reveal what we did.

Most of all, I’ve written this book to remind us that there is no comfort in bitter secrets, no grave deep enough to bury the past. It always comes back to haunt us. The only way to escape it is to go looking for it.