Feeding the Birds

Thoughts on the moral ascending character arc

Let me tell you about the time I shot a bird.

I had a very rural upbringing. I grew up in Eastover, South Carolina, one of those perpetually small towns in the Deep South. Aside from a brief surge in the 1990 census, the population has never broken 1,000 people, and the town is smaller now than it was sixty years ago. The median household income is somewhere around $23k, and probably won’t budge any time in the near future. A third of the residents live in poverty.

It was, honestly, a magical place to be a kid. The woods started at the edge of my backyard and went forever in every direction. When my dog died, my parents told me to pray for a new one, so I did. Two weeks later, a German Shepherd mix wandered into our backyard, which put my parents in the awkward position of explaining that this wasn’t necessarily the dog I’d prayed for, and that we should probably check to see if he belonged to anyone else (he didn’t). We named him Jake, after the country song, and he was my best friend for the next eight years.

Hunting culture is big in South Carolina. Every single adult male in my life was obsessed with it, which meant that I was obsessed with it. I was too young to go hunting, though, so I mostly just walked around the woods throwing rocks and screwdrivers at wild animals, because children are basically psychopaths. At some point, my dad realized it was only slightly less unhinged to buy me a pellet gun and teach me how to shoot it. I practiced in the front yard, because Eastover, SC is the kind of place where you can shoot cans in your front yard without bothering anyone.

After a few weeks of careful supervision, my dad took me out hunting. Even as a kid, I understood it to be a rite of passage, some liminal space between my up-until-now childhood and the world my dad occupied. We drove for about fifteen minutes before my dad parked the truck and led me down a walking path into the woods. A few minutes later, I spotted a bird sitting on a branch.

I lined up the shot like I was taught: lean forward; pick something small at the center of mass; inhale, exhale; squeeze the trigger instead of pulling. I fired. The bird dropped out of the tree.

We went over to look at my kill, but in my excitement, I hadn’t put enough pressure into the pellet gun. I’d knocked it out of the tree and probably broken its wing, but I hadn’t actually killed it. We stood on either side of it, and it flapped its wings once before holding still.

My dad explained that it would be cruel to leave it there, but now that I was close enough to watch it breathe in and out, I had a predictable change of heart. I was sorry that I’d hurt it, and I didn’t want to hurt it more. But I also understood that it would suffer more if I left it there to die. I loaded another pellet and pumped air into the chamber until I was sure the next shot would kill it.

I was probably seven or eight years old.

In March of 2024, I began keeping a journal of all the birds I saw throughout the day. I wrote with an audience in mind, mostly out of habit, but I wasn’t aiming for any level of scientific rigor. By way of example, here’s my entry for May 30th of last year:

Thursday, May 30th, early evening, Prospect Ponds Natural Area

Went for a walk just after a light rain and saw barn swallows diving and swooping around the train tracks. No geese today, so we were able to do our usual circuit around Catfish Pond. The Poudre River is probably at its high mark for the year, but still brackish and slow. On a clear day, you can see snow up in the mountains, so we still have plenty of snowmelt coming. The lilacs are done blooming, but the lindens have started to put out their flower stems, which look like pale leaves, and a few trees have started to put out blossoms along the river bank.

We heard the usual red-winged blackbirds and American robins, plus a handful of blue jays on the southern bank of Merganser Pond. As we circled around Catfish Pond, we kept startling the same great blue heron over and over. He’d see us, fly about twenty yards further up the bank, and wait for about thirty seconds before getting nervous and flying away again. Funny bird.

On the way home, we spotted about fifteen adult geese on the banks of Skunk Pond.

Writing about birds every day changed the way I saw the world. I watched the chickadees and finches in my neighborhood move from tree to tree as the seasons changed. The once-inscrutable tapestry of birdsong slowly resolved into the harsh alarm cries of Blue Jays, the one-note kyeer of a Northern Flicker, the punctuated chirps of Red-winged Blackbirds. I bought a bird feeder for the front yard, and I got very excited about Sandhill Crane migrations.

I also started my Substack a few months into this project, and wouldn’t you know it, my very first post was about a bird. My first flash fiction of the year also featured birds as an important plot point. I still balk at the “birder” designation, but there’s a clear distance between the person I was as a child and the person I am now.

So what happened?

Humans love narrative structures, and a writer would probably recognize this one as the “moral ascending” arc. A screenwriter could tell this story in five minutes. Put a kid in the South Carolina woods with his dad, zoom in on the injured bird in the leaves, let the kid’s finger waver on the trigger just before he puts the poor creature out of its misery. If we trust our audience, we can skip the Twenty Years Later slide and open with a side profile of a twenty-something ornithologist doing field research.

The audience can fill in the rest. The child, no doubt disturbed by his act of thoughtless cruelty, sought to learn more about the natural world and now spends his life researching birds. Got it.

But that isn’t what happened, at least in my case.

Sure, there were a handful of shifts along the way. When Ged learned about “the eyes of animals, the flight of birds, the great slow gestures of trees,” a bit of that rubbed off on me. I read a book or two by Frans de Waal, I read the same articles about intelligent blackbirds that you did.

But there were no sudden flashes of insight, no great moral epiphanies. I didn’t care about birds at all. Then, slowly, I did.

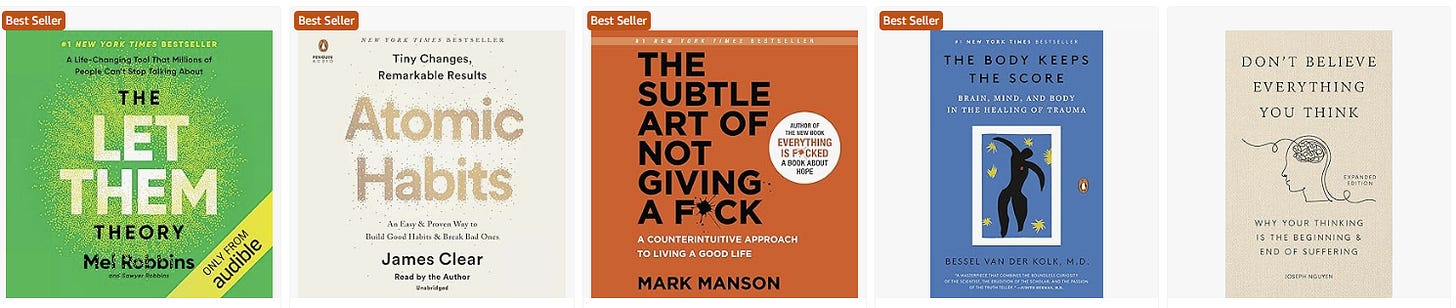

Search on Amazon for self help books, scroll past the sponsored books to the recommended titles, and you’ll see a row of covers like this:

Each promises some profound new way of thinking that will change your life. They appeal to the familiar narrative structure of a moral ascending arc, where a single profound epiphany results in changed behavior and ultimately gives the protagonist (you) the key to clearing the obstacles in front of them.

But I don’t think it works that way in real life. Alcoholics don’t have a moment of stunning clarity that fixes everything. More often, a gradual change in behavior gives them the post-recovery clarity to look back and reflect on just how far they’ve come. The epiphany comes after the change in behavior.

By the same token, I didn’t start writing about birds because I cared about them; I started caring about birds because I wrote about them. The “moral ascending” arc makes for compelling narrative, but conceals a more realistic and accessible truth: one where changed behavior gives way to new, profound ways of thinking about the world.