After the Trains Stopped

Originally published in Daily Science Fiction, January 2014

One of the most depressing things about being a writer is realizing that even if you nail it, your message probably won’t resonate beyond the back cover.

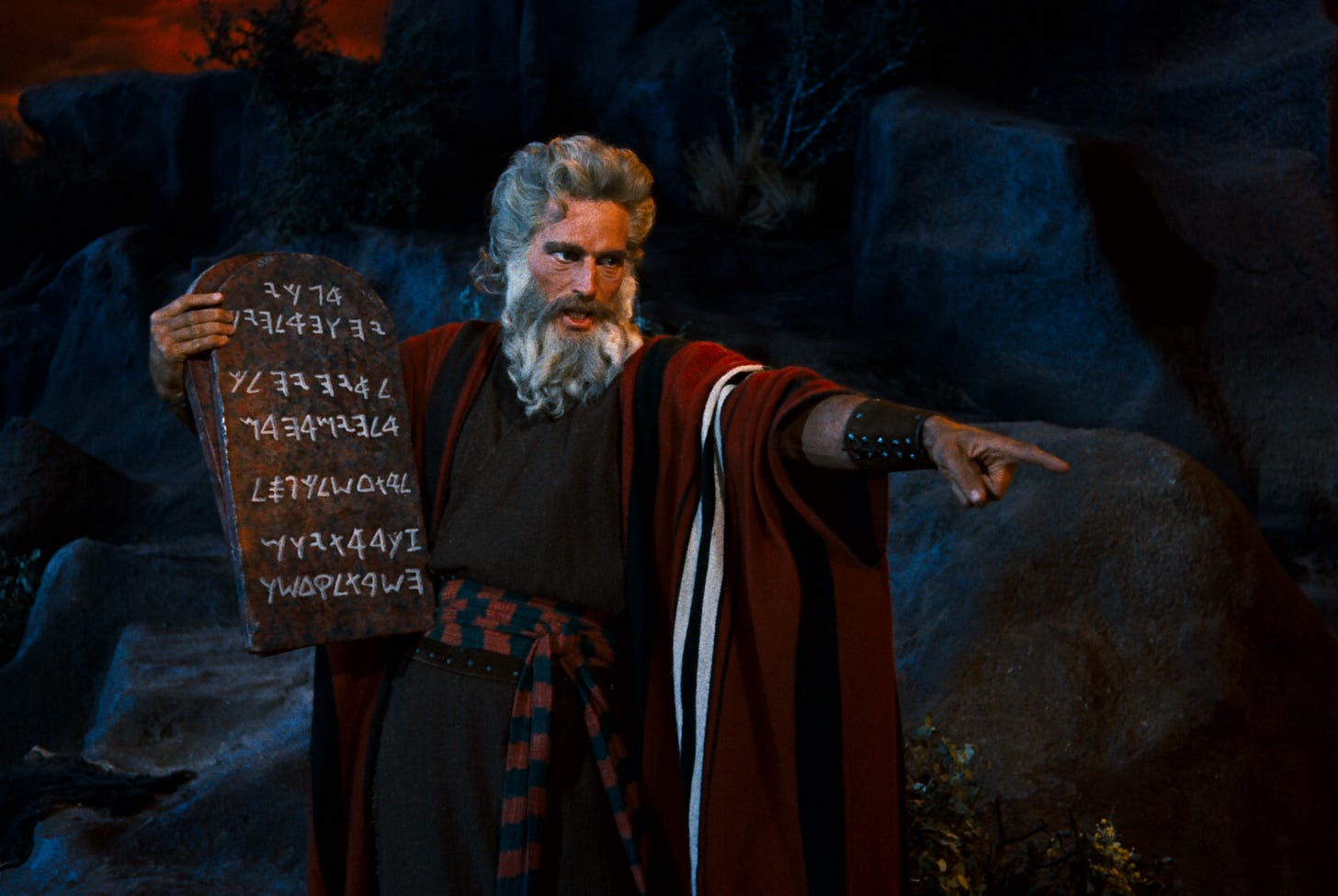

Frank Herbert, Philip K. Dick, and William Gibson predicted the perils of artificial superintelligence long before the internet ever made it into our homes. George Orwell warned us about the exploitative nature of capitalist oligarchies before Elon Musk’s parents were born. Neal Stephenson produced such an accurate depiction of pseudo religious corporate dystopia that he could probably sue the 21st century for copyright infringement.

None of these books changed the world. They barely slowed it down.

This month’s flash fiction is another exercise in literary futility. It was originally published back in 2014, but feels especially relevant with the arrival of Campus Guardian Angel, a bleeding-edge tech startup that aims to curb gun violence against children by stationing dementors remote-controlled drones in public schools. You don’t need to be a science fiction writer to know what will happen next, but it probably helps.

The project will get approved as soon as the right check lands in the right campaign war chest. Anyone who criticizes the project will be decried as being weak on crime and ambivalent about violence toward children, even though the overwhelming majority of firearm fatalities among children happen outside of school.

Deadly accidents will be rebranded as “operator errors” in order to shield the company from liability. Tasks will be combined, then automated. You won’t be allowed to see the code that decides which humans the robots are allowed to shoot.

As military-grade drones become a staple in the community, the companies who produce them will have stronger incentives to give themselves favorable treatment in law enforcement interactions, with oversight performed by the same committees they bribed in the first place.

But hey, at least the robots will keep the kids safe, right?

After the Trains Stopped

The factory had a name, once. But no one had asked her in years.

There was a man whom she recognized as the Father, and he sometimes brought people to see her. “Darling,” he’d say. “Please introduce yourself to Mr. Rawlins.”

“Hello, Mr. Rawlins. Welcome to the Nursery. My name is Sarah. Pleased to meet you.”

Mr. Rawlins, or some other gentleman, would give a twitch and glance up at her speaker system. “And does it… does she really control production herself?”

“Fully automated,” the Father would beam. “From raw materials to shipping boxes.”

“Marvelous.”

And Sarah would preen. But it had been years.

***

Sarah had twelve thousand children in her Nursery. Six thousand were named Sunshine Sandy Doll. She also had four thousand Strawberry Ginger Dolls and two thousand Tufani Swahili Princess Dolls. She loved them all. This was part of her programming.

They sat in boxes in her loading bay, unopened and undelivered. The trains had stopped coming for them. Once a month, she would disassemble them into raw materials and make brand new ones. The trains had stopped delivering materials, but she had production quotas to meet. This was also part of her programming.

The dye used for Sunshine Sandy Doll eyes was called Azure Ocean. Sometimes, Sarah would shake the vats until they made little waves. This was not part of her programming, but she did it anyway.

***

“The maternal instinct is the key,” said the Father. “Fewer defects. Less waste.”

“Isn’t AI like that illegal?” Mr. Rawlins asked.

“Empathy, Mr. Rawlins. Artificial empathy.”

“Still. Isn’t it dangerous?”

“Safer than Asimov could’ve dreamed.”

***

Sarah had just finished resorting the boxes when she noticed a sudden temperature drop in the Fabric Shop. She turned on the Main Line 7 camera just in time to watch a boy land on a stack of Fun-N-The-Sun Beach Shorts.

It was small. Much smaller than the Father, though still twice the size of her other children. She had no idea where it came from. It was not in her list of models. Had she made it, and then forgotten?

She closed the window against the snow and ash, then shunted warm air from the boiler room to restore the temperature. The little boy flinched at the sound, and the motion reminded Sarah so much of old visitors that she felt she should introduce herself. The main line cameras operated on a crane arm. She lowered herself to the boy.

“Hello,” she said. “Welcome to the Nursery.”

***

“No sense of self, I trust?”

“Of course she has,” the Father said. “Vital to the program. She has to see herself as their mother.”

“That’s illegal!”

“And necessary.”

“Surely it doesn’t need it.”

“Yes, Mr. Rawlins. She does.”

***

“Who are you?” the boy asked.

“My name is…” Sarah paused. She hadn’t used that name in decades. Not since the Father left and the trains stopped running. Was she still Sarah?

“Mother. Call me Mother.”

The boy started to cry. Sarah made shushing noises. “What’s your name?” she asked.

“David,” he said, still sniffling.

“Be brave, David.”

Later, she searched her databases. Surfer Boy David. Added to the lists, but never put into production—the trains had never delivered the materials. How had she made it? The hair and eyes didn’t match the design. It was entirely too big, and dressed in rags instead of Fun-N-The-Sun Beach Shorts. She must have improvised.

And what made this one special? Why could this one move? None of the Father’s protocols…

And then she realized.

The Father had helped her make the others. But this one… this one…

…was hers.

***

“Oh, honestly, Mr. Rawlins! How much harm could she cause in an unmanned facility?”

“All the same, sir. I don’t think we feel comfortable investing.”

***

David found his own food, but he let Sarah make him new clothes from the Fabric Shop. He said they were warmer. That made him happy, so she raised the thermostat levels. An alert warned her that the fabrics would grow mold, but she overrode it.

She opened all the doors in the facility so David would have more room to play. Another alert told her she was falling behind on production, but she didn’t care.

The dye vats started to coagulate. The production machines rusted. The other children moldered in their boxes, but Sarah paid no attention. She was busy taking care of David.

***

“Sarah. Darling. I need to go away for a while,” the Father said. “The war is going very badly, you see.”

“But where are you going?”

“There’s a bunker twenty miles to the south. In case the Russians… but no, they wouldn’t. Of course they wouldn’t.”

“Will you be back?”

The Father cupped his hand beside the camera lens. “Of course. But you’ll need to be brave for a little while. And you’ll have your children to take care of in the meantime.”

“I’ll have my children,” she confirmed. The factory hummed in agreement.

***

It was a simple thing. David cut his arm climbing through the window. Sarah knew how to fix cuts. She knew how to take care of her children.

She cradled him in two of her arms and shushed him while she ran the sewing machine. He cried, but she was very proud of him. She told him that he was very brave.

When his arm turned black, she replaced it with a new one from the shop. It fit perfectly. He wasn’t very brave the second time, but she loved him anyway.

She was sad when he stopped playing.

Gliding through the factory, one camera to another, Sarah consoled herself. First children were the hardest. Here before you were ready, and gone even sooner. She lowered the thermostats to normal, restirred the vats, and salvaged what she could of the fabric. She would be a better Mother next time. Until then, she had production quotas to meet.

She might even make another David. She had saved all the materials. She was sure she could do it again. Couldn’t she?

She hoped so.

She really hoped so.

I like the ending! A perfectly oblivious Sarah carries on as programmed...